What I've Learned from a Decade of Cartooning

Though I’d yearned to cartoon since I was a kid who read daily newspaper funnies, and dabbled a bit in grade school on lined paper, I was intimidated by the idea of laying out a comic page. For some reason I thought there was a mathematical formula to laying out a comic page, and even basic math completely eludes me.

It wasn’t until I was about 25 years old that I drew my first full comic page, after some brief counsel from my neighbor Noah Van Sciver who dispelled the notion that there was a mathematical formula to laying out a page. I don’t remember exactly what he said but I basically learned “just draw boxes.”

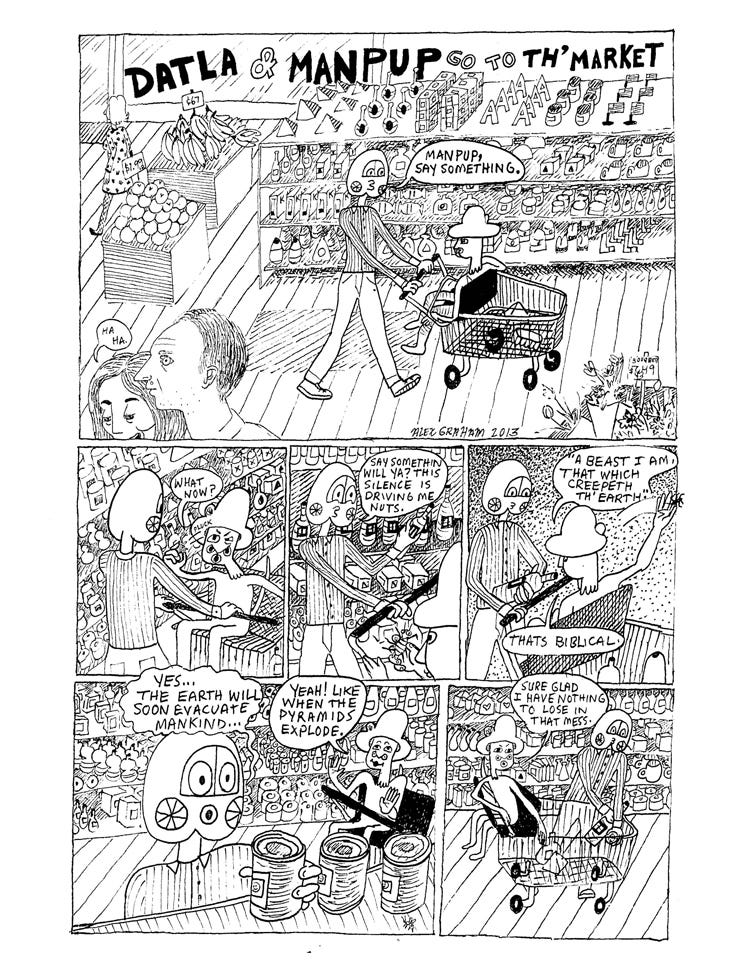

For those first five years of cartooning as an adult (age 25-30) I wasn’t worried about perfection in either my writing nor my drawing; as any author knows, you need to get your first book out of the way and try not to get fixated on the details, or you’ll never get through it. I would flip through my 10 copies of Weirdo and attempt to emulate Aline Kominsky Crumb, or Dori Seda (whose cartooning at that time was way above my ability and left me awestruck). Robert Crumb to me at that time was a god whose level of craftsmanship I was sure I would never touch, so I didn’t dare try.

I drew with dried-out microns and my motto was “faster, faster, draw faster! It doesn’t matter, just push through!” Which is good, in my opinion, for a cartoonist’s first effort. It’s not going to break the world, just get through it.

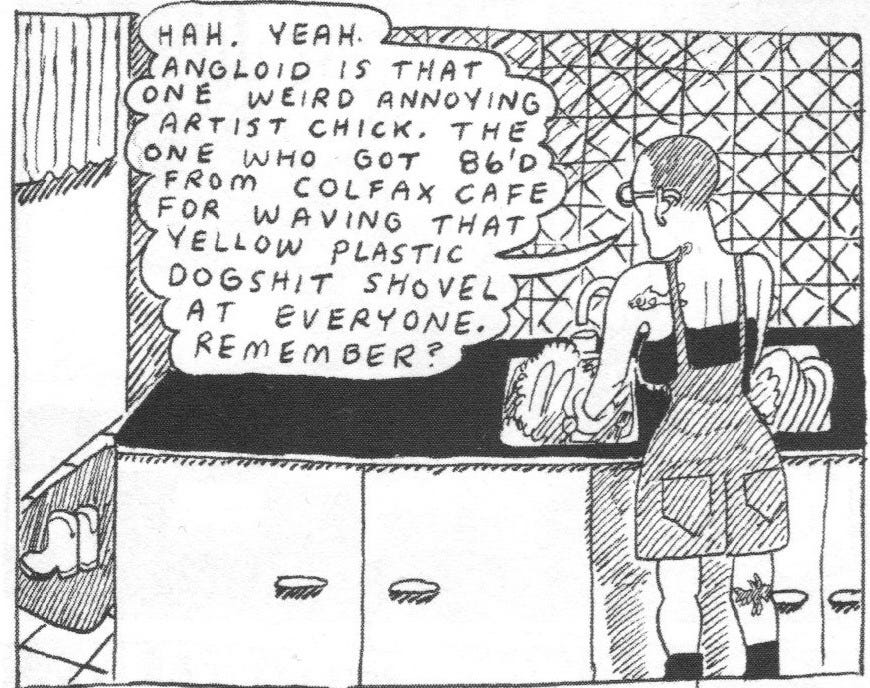

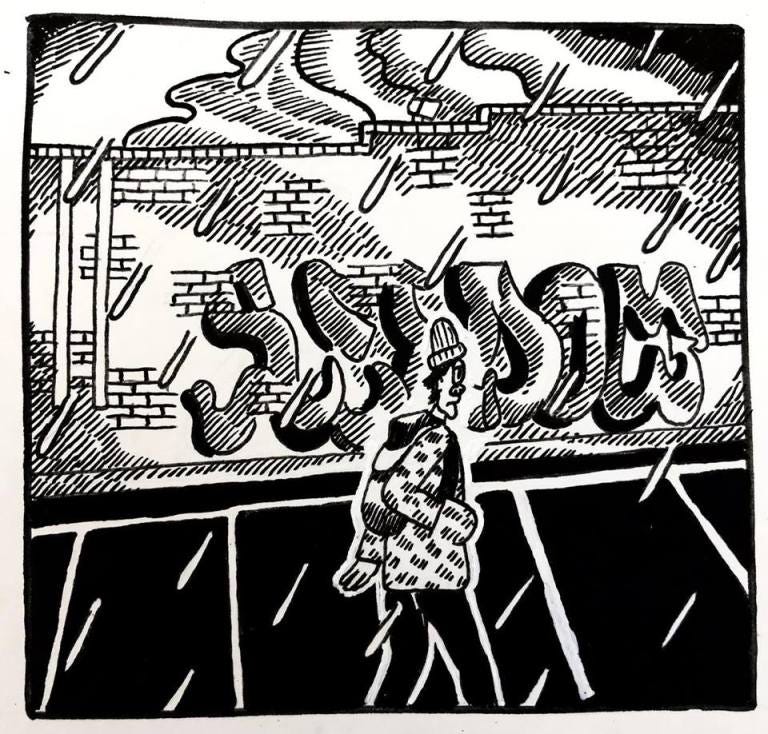

I worked on my first book Angloid (Kilgore, 2018?) for 5 years. The first two years were spent laying out a storyboard and simultaneously living the story. Young people take note: don’t spend your entire 20s sitting at a drawing desk. You gotta live an interesting story. Get your heart broken. Evade death several times. Go smoke cigarettes after bar close with a gorgeous sex worker in an alleyway until your vision swirls and you forget who you’re even speaking to and what gender they are. Stand at a dark street corner on a freezing cold night at 3 am waiting for a cab that never comes and drink out of a friendly homeless person’s Aquafina bottle full of vodka and orange juice. Wait, don’t do that!!

Even though I knew in the depths of my mind that Angloid was merely practice for more important and fine-tuned cartooning later down the road, when it was finished, I was certain that it was the most important thing I’d ever accomplish in my life. It was groundbreaking. It would be a movie someday. “I can die happy now,” I thought. I was totally blind to its imperfections. It was perfectly drawn. I would read it over and over, laughing at my own jokes, totally self-satisfied. Now, in 2023, I can’t even look at that book, though I acknowledge it still has value—especially because I recorded many things that actually happened to me during that time.

The official Kilgore edition of Angloid came out right when I moved to Seattle in early 2018. Shortly after, I began hanging out with local big shot cartoonists. Looking at their work up close gave me a huge shift in perspective. Suddenly my drawings appeared more scritchy-scratchy and slapdash in comparison to the work of my (now) contemporaries.

It’s not that I had to undertake a huge overhaul of my methods… the only thing I really had to do to bring my work up to par was…. SLOW… DOWN. Draw slower and with more intention. Think more carefully and with purpose about the words in my dialogue.

Within just a year, I’d leveled up my drawing abilities by a staggering amount. Of course, some Marvel and DC snobs would argue my drawing style still sucks dick. That’s fine, it’s not for everyone.

And now I’m at a point where I’m pretty happy with my cartooning, although I’m sure in 5 years I’ll be even better, and I’ll look back and see tons of flaws.

But, no matter how much I try to “control” my style to measure up to my new standards of perfection, sometimes my old style still slips through. I can even see remnants of the way I used to draw as a child peeking through at times. I try not to be too frustrated by it, or do too much over-correcting, lest I polish away the thing that makes my work unique, or erase my inner-child.

Now I’ve arrived at the bullet point part of this article. Here are some things I’ve learned that may be of use to others:

Readability is of the utmost importance. Your audience should never have to stop and squint at your lettering. Avoid using heavy serifs or stylized lettering, cursive*, or anything that gives your reader pause. Write big rather than small. Speaking of size…

Don’t print your comics too small. I personally don’t like the feeling of having to pull your comic page closer to my face to be able to read and comprehend what’s happening.

It should be clear at all times who is talking. Your speech balloon tails should point clearly at whatever character is speaking, so that the reader can comprehend with just a subconscious glance where the speech is coming from.

Each of your characters should have a distinct look. Characters who too closely resemble each other can create frustration and confusion for your reader.

Pacing - DON’T BE IN SUCH A HURRY to tell your story that you skip over important little details that humanize your characters and circumstances. Take your time - one of the beautiful agonies of being a cartoonist is that you will be stuck inside a single moment, a single gesture, a single expression, that in real life might occur in 30 seconds, but you are TRAPPED in those 30 seconds for the entire day. As agonizing as it is, it’s a good thing. Relish the process! Take it one day at a time, and in a couple months, you’ll look back upon a compelling story with lots of nuance in every facial expression, every word, every sigh, every bite of food eaten, every object held.

*some people can pull this off, but not many.

The overarching lesson of my bullet points is this: Comprehension of your cartooning and storytelling falls on YOUR shoulders and is 100% YOUR responsibility, not the responsibility of your reader. Your audience should not have to work AT ALL to understand what is occurring. Do not make your reader work or you risk losing their attention. An unfortunate thing to keep in mind in the year 2023 is this: you are competing with a smartphone for your reader’s attention. Don’t let them reach for their phone!

As long as you keep these points in mind, you can do whatever you want. I left out things that are purely my own preference, such as over-narration.

If you’ll allow me to do some editorializing: I personally don’t care for comics that lean heavily on narration, and I won’t read them. But I understand that that’s a stylistic preference on my end, and such comics can still have value.

Of course autobiographical comics can be of value, and there are some great cartoonists doing autobio comics even now—Sam Szabo, for example, is making work that is well-paced, doesn’t take itself too seriously, has great comedic timing and is an absolute pleasure to read. But IN MY OPINION the culture is oversaturated with autobiographical stories, which is one of the many reasons I pivoted away from the genre after This Never Happened (an abandoned storyline from 2019).

As someone who has extensively dabbled in both autobiographical and fiction cartooning, please believe me when I say that writing fiction is so much more fun. Fiction storytelling allows one to sneak elements of one’s own life into the story, but it leaves a comfortable amount of room for interpretation. Sometimes autobiographical cartooning can feel uncomfortably intimate.

Autobiographical cartooning can also create a feedback loop in the author’s life where they feel they must act like the character they’re portraying. If that character is an abusive asswipe with substance abuse issues, what do you think the author might feel compelled to do in his or her own life?

Above all: create from your heart, tune in to The Source and pull ideas from the collective conscience, find a spiritual center to your art practice and learn to enjoy solitude. I enjoy my solitude as a cartoonist and painter because my characters are my children, and I get to escape from this barbaric world for just a moment—but it’s a moment worth living for.

And with that, I’m off to work.

AG

Thanks for this essay - it gives me a lot to think about as I try to get my cartooning really up and running (as an old man, unfortunately, but I'll do the best I can).